The Edge Land Development Company

The Edge

The first new successful urban planning system in the US in over 100 years.

by Douglas Swallow on January 14, 2020

The first generation of this urban planning system enabled The Howard Hughes Corporation to turn the largest underperforming master-planned community in the US, Summerlin in Las Vegas, Nevada, into the fastest-selling new town in America and one of the most financially successful. And in the process become the first master-planned community in over 60 years to eclipse the 3,000 home sales per year rate in one location. This post introduces this platform and takes approximately 15 minutes to read.

The Edge is a smart growth non-zoning-based residential and non-residential streetscape-based planning platform. At its core is a local economy aligned, market-driven, lifestyle, value orientation, and stage of a life-oriented residential programming platform that enables large-scale land developers and city planners to plan their projects and communities more effectively than zoning-based platforms. Its retail, office, and light industrial are centralized versus decentralized and strategically placed based on rooftops and other commercial and non-residential components. This new methodology presents a highly effective way to create top-performing sustainable communities that have a positive social and environmental impact on their residents and business owners.

The system classifies large-scale planning areas into four groups:

1. Greenfield

2. Existing town, city, or county

3. Infill

4. Brownfield

In this context, a greenfield site is defined as one within or outside of a city that has not been previously developed. It may or may not be in a rural area or currently being used for another purpose, such as agriculture. Existing town, city, and county planning areas include all areas adjacent to the respective entities’ comprehensive or general plan. Infill development refers to an undeveloped site within a developed community of urban environment. Also, it includes demolition sites, where existing structures on a site are removed for new buildings or alternative use. According to the EPA, Brownfield sites are those in which “the expansion, redevelopment or reuse of may be complicated by the presence or potential presence of a hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant,” such as industrial, military, or agricultural sites.

The size of a planning area was a critical variable in the achievement of optimal fiscal performance. As with all systems, there is a size and velocity at which a system performs optimally and a point at which the return on investment begins to diminish. The concept of optimal master-planned community sizing is based on critical mass and financially supportable absorption windows.

The optimal size was found to be 600 to 800 acres. The 600 to 800-acre increment typically allows for the full breadth of residential products from entry-level and apartments to executive homes, thereby optimizing absorption schedules. At this size, a mostly residential master-planned community can be developed and built-out in five years, which creates a financially supportable and viable development scenario for developers, investors, lenders, utility and infrastructure, and other city service providers.

One of the more interesting discoveries in this sizing model was its relationship to schools. One 600 to 800-acre residential master-planned community supports one elementary school, four support one intermediate school, and seven villages support one high school.

By definition, the word “village” is a planning area smaller than a town. The term “village” entered the vocabulary of land development as a planning variable in the mid-1990s with the introduction of multiple master-planned communities (MPC) within one MPC. Before multiple MPC’s in one MPC, the term village was used mostly as a community advertising term.

In this discussion, the term master-planned community (MPC) is used to denote MPCs made up of two or more villages. The term village describes a specific planning area containing a specific set of residential, non-residential, and governmental product types. Furthermore, each village has its own unique lifestyle and economic profile, which is supported by a matching land-use allocation strategy and defining edge condition.

The term “edge condition” traditionally refers to the streetscape; however, in this context, it refers to a specific type of streetscape-one that is in alignment with the lifestyle of a village type. Specifically, edge conditions deal with street and sidewalk design, quantity and quality of landscaping in the median, and the quantity and quality of landscaping between the curb and the wall or structures. Edge conditions also embrace the disciplines of community entries, signage, open space, amenities, and lighting. The under-specification of these factors can negatively impact the development and, subsequently, the community and its sense of place.

The term “residential neighborhood” is used to describe home building projects. The term “development” is used with retail, office, and commercial projects.

The traditional zoning-based planning methodology is characterized by broad land use allocations versus specific socioeconomic village-oriented allocations. In the traditional methodology, residential land use allocations are delineated by density category (e.g., low medium, high, and or by lot size.) Non-residential land use allocations in the traditional methodology are also broad (e.g., neighborhood commercial, community commercial, regional commercial.) Conversely, The Edge aligns a mix of villages with the community’s and regions economic and socioeconomic profiles.

Within the greenfield classification, there are five types of planning areas:

1. Single village

2. Multi-village

3. New town

4. Multi-new town

5. Metropolitan area

A single village is one 200 to 800-acre planning site. Multi-village sites are those with two to five villages or up to 3,000 acres. New towns typically range in size from 3,000 to 30,000 acres. The multi-new town classification is used in sites typically over 50,000 acres, such as the Irvine Ranch in Southern California. Irvine Ranch is approximately 93,000 acres and is comprised of 47 residential and three commercial villages. The community encompasses the city of Irvine and parts of seven other cities and unincorporated county lands. Metropolitan areas include one urbanized city with more than 50,000 population and multiple jurisdictions and municipalities that share infrastructure, transit systems, and primary arterials. The smallest metro area in the US is the Reno-Carson City-Fernley in Nevada. It has a population of just over 55,000. The largest is New York-New Jersey- Jersey City, with more than nineteen million inhabitants.

This platform operates on one of three financial classifications:

1. Investment

2. Legendary

3. Community development

The investment platform’s focus is to acquire, entitle, sell, and achieve a superior annualized return on investment (ROI).

The legendary platform is quite different; its primary objective is to create one of the world’s best communities in its class. The platform places net revenue and returns on investment (ROI) second to design, edge conditions, amenities, infrastructure, and design and development standards.

The community development platform enhances general and comprehensive plans and business development opportunities through lifestyle-based village typing, thereby enabling them to create highly desirable, safe, and sustainable communities more effectively.

Investment groups, corporations, builders, and developers tend to invest in projects which operate on the investment platform. The legendary platform is typically employed by individuals of wealth, estates, cities, governments, institutions, and philanthropic organizations. Municipalities almost exclusively use the community development platform.

There are nine types of residential villages and 34 market segments in The Edge. Each village type has a specific land-use allocation model and set of residential market segments. The nine types of residential master-planned communities include:

1. Luxury

2. Active adult

3. Resort

4. Urban

5. Traditional neighborhood development (TND)

6. Amenity

7. Non-amenity

8. Rural

9. Whole life

The twelve types of non-residential villages are town center, recreational, urban, airport, port authorities, industrial, prison, military, stadium, and three campuses: educational, office, and governmental. Within these non-residential villages are 42 market segments.

Supporting the platform is the advanced residential market research and mapping system called SweetSpot. This system holds there are 27 natural residential market segments: nine single-family detached, nine single-family attached, and nine custom lot. Each market segment is defined by a combination of density, setbacks, side-yards, height limits, minimum lot size, lot coverage, bulk plane setbacks, square footage, lifestyle, and homeowner economics. All of these are combined into a straightforward land development strategy formulation system that defines the optimal development strategy and integrates it into a budget, financial proforma, schedule, and business plan.

Creator of The Edge

Hello, my name is Douglas Swallow. I developed the idea for The Edge while working for The Howard Hughes Corporation as Summerlin’s Vice President of Marketing in Las Vegas, Nevada. In the summer of 1993, I joined the management team. I had just finished up a 7-year stint at one of the most award-winning master-planned communities in the industry’s history at the nearby luxury golf course community of Spanish Trail, where I lead the sales and marketing operation. Upon my arrival at the company, I was tasked with managing its 7M dollar per year marketing budget, leading the custom home division, and creating the design, development, and signage standards.

To date, I have worked on 44 master-planned communities in 121 cities throughout California, Nevada, and Arizona created the development strategies for 11 of the last 15 major master-planned communities in Las Vegas, and been the lead expert witness in the largest civil lawsuits in Nevada’s and Utah’s history.

More recently, I used the methodology to program a new 110,000-acre metropolitan area with seven cities, 91-residential villages, and 9-non-residential villages. The over 100-billion-dollar project with over 30 billion in infrastructure costs is scheduled to have over 40,000 acres of parks, trail systems, and open space and be home to nearly 500,000 people.

Summerlin

In 1993, Las Vegas, Nevada, was the US’s hottest housing market and it had more master-planned communities than any city in the world, with 21 active communities. The largest community was Summerlin. It spanned the entire west side of Las Vegas. It was fifteen miles in length and four miles wide at its widest point. It began with 25,000 acres; just over 2,500 were sold-off to off-set initial development costs. The remaining 22,380 acres were then divided into 30 master-planned villages. At buildout, the community was scheduled to have 80,000 homes, 250,000 residents, and over four million square feet of retail, office, and light commercial. Summerlin was the second-largest master-planned community in the US behind Donald Bren’s Irvine Ranch at 93,000 acres.

When I joined the team, the community was under development for seven years, but there was a little problem. The community was absorbing 250 acres of land and selling approximately 600 homes per year—excellent numbers for any master-planned community developer, but not The Howard Hughes Corporation’s shareholders. At the time, the community had 18,000 acres to go, and based on development strategies created by the world’s leading consultants, it would require over 70 years to complete.

The problem was the heirs and critical stakeholders were in their 60’s and the water entitlements for the project were scheduled to run out in 18 years. This would have left 13,500 acres undeveloped and approximately 2.7 billion dollars on the table. As a result, the leadership needed to find a new absorption model that could produce annual sales of more than 3,000 homes and absorb 1,000 acres, a feat only achieved at one other time in largescale land development history, which was at Levitt Town following WWII in the early 1940s. Unfortunately, the secret to selling, building, and closing over 300 lots and homes per month in one location for nearly three years, out of one 700 square foot sales office, was lost with the owners’ passing.

However, a solution to the stakeholder’s problem was identified to formulate this new planning methodology. The planning methodology that would go on to become The Edge.

The idea for the new planning platform emerged at a site-planning meeting at the offices of the land planning firm of PBR in Los Angeles in the summer of 1993. The planning team and I were programming the southern third of the community (Actually, they were, I was just along for marketing support). In attendance were over a dozen of the world’s leading experts in urban planning. On the wall was a large map of the community and its supporting road and infrastructure network.

At the meeting, I was sitting off to the side; as they were working on the macro engineering plan, when, in my mind, I began to apply the new theories of market segmentation and consumer value orientations to the copy of the large map of the community that was on the wall.

The market segmentation theory held there were specific market segments within major product categories such as hotels, automobiles, housing, etc. These segments could be further divided by consumer’s innate value orientations, i.e., lowest total cost solution, best total cost solution, and highest quality cost solution. The theory had proven that those products that crossed over segments and value orientations performed at much lower levels than those that adhered to the specific parameters.

The production builders I had worked with had found they could triple their absorption rates, increase revenue, and significantly reduce risk with this theory. They found the best way to do this was by dividing their larger parcels into distinct market segments, as defined by the stage of life neighborhoods, i.e., young family homes, 1st move-up family home, mature-family homes, etc.

Which got me to thinking, what if we applied the same theory to large-scale planning areas? What if there were different types of master-planned communities, i.e., planning areas that were distinctly different and non-competitive, which would allow for multiple planning areas developing at the same time?

Thus far, five villages had been developed in the northern part of Summerlin, two by Del Webb as active adult communities, and three as traditional amenity-oriented master-planned communities. The southern part of Summerlin was scheduled to be made up of 7,000 acres and eleven villages.

On the back of the small site plan, I quickly began to list different types of master-planned communities. There were two already on the wall, retirement and amenity. I had just come from the best-selling luxury master-planned community in America, so there was the third. Then having been raised in Walnut Creek, California, a rural town 30 miles due east of San Francisco, I realized there would be a rural village. Next, having had the opportunity to travel to the Hawaiian Islands, I identified the resort master-planned community. And lastly, I noticed there would be one more, an urban village.

Then I wondered, what if we had all seven types of villages going at the same time in the north and the south? It turned out we could. Further analysis revealed we could develop eleven villages simultaneously without cannibalizing sales and achieve annual sales rates of four to six hundred homes per village or 4400 to 6600 per year.

A couple of months later, the concept was introduced to the board of directors, and despite its staggering cost of over 250 million dollars, they unanimously approved the idea. A month later, I was asked to introduce the concept to the industry at the Urban Land Institute’s (ULI) fall conference at Harvard University.

The idea’s implementation resulted in increased annual sales in one location to over 3,300 homes and 1,000+ acres. The residual land price per acre went up 30% above the market average, and the financial fortunes of the company were radically reversed. The community would become the gold standard in “smart” cities and lead the nation in sustainable, socially, and environmentally conscious communities.

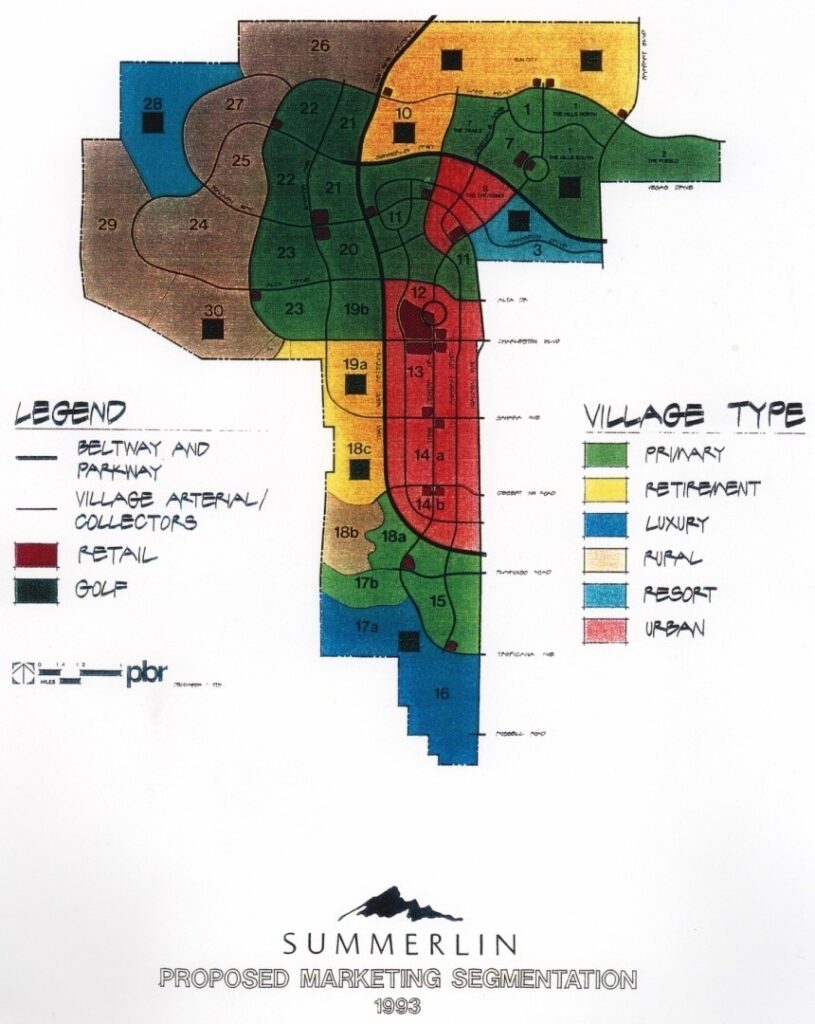

The following is a copy of the village or master-planned community typing overlay of The Howard Hughes Corporation’s Summerlin that came out of that Los Angeles planning meeting in the summer of 1993. The exhibit shows Summerlin divided into 30 master-planned communities using seven types of master-planned communities. The 30-master-planned community strategy consisted of 7 Rural, 15 Traditional Amenity/Non-Amenity, 2 Luxury, 5 Active-Adult, 2 Resorts, and 4 Urban. Today, there are eight active development areas and six types of master-planned communities.

A few years later, while consulting on a large BLM landholding, it was noted by a colleague that it was the first successful new comprehensive urban planning platform in America since the introduction of the zoning-based platform in the early 1900s.

The system’s name came from the observation that each type of master-planned community had a different landscape pallet unique to each type of residential master-planned community. The most defining element of these landscape designs was the perimeter edge conditions, which framed each community and defined its sense of place, hence The Edge.

Landscape edge conditions define socioeconomic, demographic, and lifestyle preferences. Through the manipulation of these edge conditions, developers can:

1. Lower development risk

2. Increase land values by up to 30%

3. Accelerate annual absorption rates by up to 400%

4. Protect land values

5. More effectively raise equity and debt

6. Manage development velocity

7. Enhance the standard of living

8. Protect the quality of life

9. Reduce the public fiscal impacts of development

10. Create socially and environmentally impactful and sustainable communities

Regional performance studies of master-planned communities found the more targeted and aligned a master-planned community was to a specific village type, the better it performed. Conversely, the opposite was found.

Smart Growth

At the top of virtually every major city’s planning agenda in America is “Smart Growth.” By definition, smart growth is the forum for urban growth, social and environmental responsibility related issues. Nearly all growing cities face the same issues of urban sprawl, traffic congestion, inadequate education facilities, inner-city and mature neighborhood decay, insufficient public services capacity, community safety issues, inadequate funding for parks and open space maintenance, and providing a sustainable foundation for economic growth.

Elected officials, county and city planners, and smart-growth constituencies have ten core responsibilities.

1. Create a regional vision all constituencies can embrace and support

2. Protect and grow the economic foundation of the community

3. Preserve and protect critical environmental areas, open space, and ensure each community has the appropriate level of park programming

4. Create a socially responsible, safe, healthy, and vibrant community for people of all ages and lifestyles

5. Create a full range of housing opportunities and types of neighborhoods

6. Encourage community and stakeholder collaboration

7. Create a general plan that magnifies and strengthens each of its communities and neighborhoods identity and sense of place

8. Create a community with a full and balanced mixed-use strategy

9. Provide a complete transportation system

10. Create a development strategy that fiscally encourages infill development

At its core, Smart Growth is about one thing, quality of life. Just 40 years ago, quality of life was not a significant issue in America. However, today the problems mentioned above have not only led to the decline of quality of life in nearly all growing cities; they now threaten their very future.

Pick your survey, the #1 reason people and companies list why they leave a town is quality of life. The cities that can create and demonstrate that they have the tools, plan, and commitment to sustain the quality of life will flourish. Those who don’t will be highly susceptible to the boom-and-bust development cycle.

How do communities solve these problems? Do they do it through:

- General plans

- More restrictive zoning

- Permit limits

- Growth boundaries

- Protracted entitlement processes

- Restrictive residential and non-residential design standards

- Developing a prohibitive economic development culture

While the solution appears to lie in its cause, growth, it does not. The problem lies in the planning platform on which virtually every city in America is designed. There are six major types of zoning-based planning systems: Euclidean, Form-Based, Smart, Incentive, Performance, and Modular. None of them were ever designed to manage growth or integrate diverse lifestyles and businesses or protect citizens’ lifestyles and cultural preferences who were governed by them.

Zoning and density-based planning are now over 100 years old. Virtually every city since the early 1900s in America has used some form of zoning. Every city is attempting to solve today’s problems with yesterday’s technology. If there is too much water going through a pipe, is the problem the volume of water, or is that the pipe is improperly sized to handle the flow? The zoning and density-based planning platform was never designed to meet the needs or demands of the 21st-century city.

The solution to today’s problems lies in creating a new platform that can easily handle rapid growth rates, protect the environment, and ensure an exceptional and sustainable quality of life. Does such a platform exist? Yes, and it’s called The Edge.

This planning platform has proven to manage growth and eliminate our cities most pressing issues effectively. It reduces urban sprawl and leapfrog development, maximizes land values, and provides communities with the ability to grow at accelerated rates without adversely affecting the standard of living or quality of life of existing constituencies. For mature and or declining areas of cities, The Edge can significantly reduce declining property values and put the areas in question on a value restoration path.

The Edge identifies long-term revenues and development costs for both the developers and elected and non-elected city officials. And for the first time, it aligns and balances general plans with their economies and their constituents’ lifestyle preferences.

The zoning-based planning platform is and has been a win-lose urban planning platform. For decades builders, developers, city planners, elected officials, service providers, and constituencies have had to interact with each other on a win-lose basis, until now. The Edge creates a win-win platform for all groups. It doesn’t replace a city’s zoning platform. It enhances it by becoming highly flexible, fiscally, and environmentally responsible, and precisely aligned with the region’s economics.

What this new urban planning system does for towns, cities, and metropolitan areas is enable them to move the local and regional planning departments from their administrative roles to that of a master developer. And in so doing, it allows them to create stronger general plans with accurate economic and tax revenue forecasts and the ability to select residential and non-residential builders and developers—just the way master-planned community and state BLM divisions do.

For more information about how you can improve the performance and quality of your master-planned community, new city, or existing city, please reach out to me at doug@orggenetics.com.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Douglas Swallow has been an innovator, intellectual property developer, author, and speaker in CEO optimization, human capital and urban planning spaces for 40 years. His body of work has led to the solution to age old mystery of what enables top-performing CEOs, managers, and employees to deliver results 1.3 to over five times their equally profiled colleagues. And more importantly, to the development of a body of knowledge and collection of technologies that equip builders, developers, and city officials create top-performing projects, communities, and cities.